Patient Education

Our Health Library information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Please be advised that this information is made available to assist our patients to learn more about their health. Our providers may not see and/or treat all topics found herein.

Topic Contents

Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation

Catheter ablation is a minimally invasive procedure to treat atrial fibrillation. It can relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

During a catheter ablation, the doctor destroys tiny areas in the heart that are firing off abnormal electrical impulses and causing atrial fibrillation.

You will be given medicine to help you relax. A local anesthetic will numb the site where the catheter is inserted. Sometimes, general anesthesia is used. The procedure is done in a hospital where you can be watched carefully.

Thin, flexible tubes called catheters are inserted into a vein, typically in the groin or neck, and threaded up into the heart. There is an electrode at the tip of each catheter. The electrode sends out radio waves that create heat. This heat destroys the heart tissue that causes atrial fibrillation or the heart tissue that keeps it happening. Another option is to use freezing cold to destroy the heart tissue.

Sometimes, abnormal impulses come from inside a pulmonary vein and cause atrial fibrillation. (The pulmonary veins bring blood back from the lungs to the heart.) Catheter ablation in a pulmonary vein can block these impulses and keep atrial fibrillation from happening.

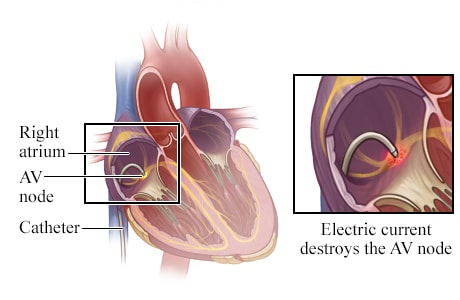

AV node ablation

AV node ablation is a slightly different type of ablation procedure for atrial fibrillation. AV node ablation can control symptoms of atrial fibrillation in some people. With AV node ablation, the entire atrioventricular (AV) node is destroyed. After the AV node is destroyed, it can no longer send impulses to the lower chambers of the heart (ventricles). This controls atrial fibrillation symptoms.

After AV node ablation, a permanent pacemaker is needed to regulate your heart rhythm. Nodal ablation can control your heart rate and reduce your symptoms, but it does not prevent or cure atrial fibrillation.

How It Is Done

Catheter ablation

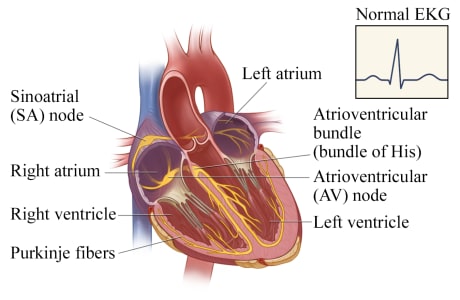

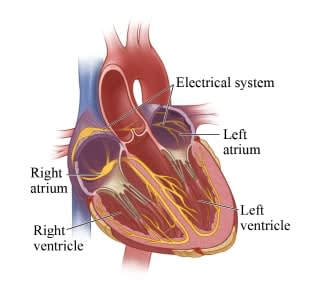

In a normal heart, the sinoatrial (SA) node triggers the electrical impulse, causing the upper chambers (atria) to contract. The signal travels through the atrioventricular (AV) node to the atrioventricular bundle, which divides into the Purkinje fibers that carry the signal and cause the lower chambers (ventricles) to contract. The electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) tracing shows this normal electrical activity.

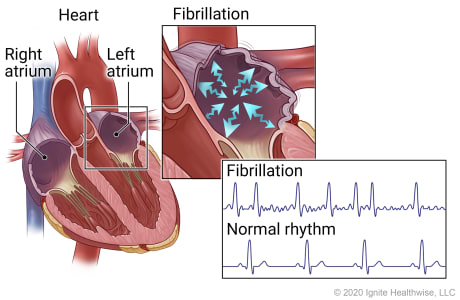

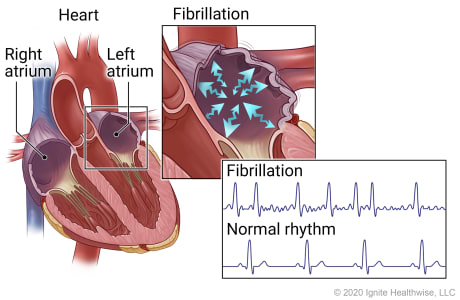

In atrial fibrillation, erratic electrical impulses can cause the upper chambers of the heart (atria) to fibrillate, or quiver, resulting in an irregular and frequently rapid heart rate. The irregular, sawtooth pattern in the electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) tracing shows these erratic impulses.

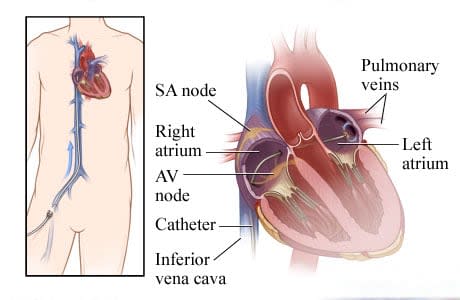

For this nonsurgical procedure called catheter ablation, thin tubes called catheters are inserted into a vein, typically in the groin or neck, and threaded through the vein into the heart. A small puncture in the tissue that divides the right and left chambers (septum) allows the catheter to pass into the left atrium.

An electrode at the tip of a catheter sends out energy that destroys (ablates) the tissue that is causing atrial fibrillation. The main types of ablation are:

Thermal ablation. This is the most common type of heart ablation. It uses either heat (radiofrequency) or extreme cold (cryoablation) to destroy the small areas of heart tissue causing the abnormal rhythm.

Pulsed field ablation (PFA). PFA uses short, high-voltage electrical pulses to target and destroy only the heart cells causing the abnormal rhythm. Since it only targets the problem areas, PFA may lower the risk of damage to nearby areas like the esophagus, nerves, or blood vessels.

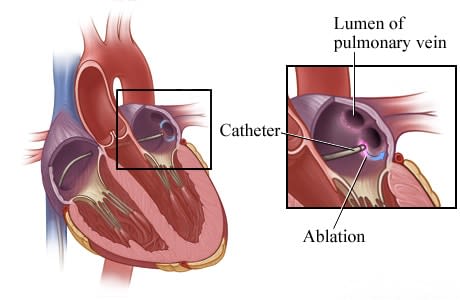

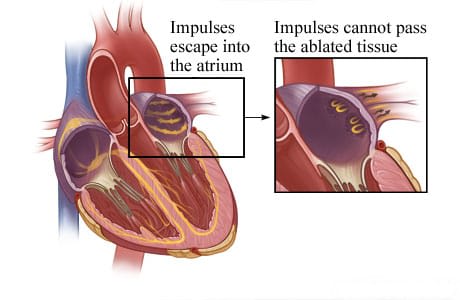

In this image, the energy is destroying tissue at the base of the pulmonary vein. (The pulmonary veins bring blood back from the lungs to the heart.)

Catheter ablation creates scar tissue that prevents impulses from leaving the pulmonary veins or eliminates the impulses altogether.

AV node ablation

In a normal heart, electrical impulses pace the rhythm at which the heart contracts and relaxes. The sinoatrial (SA) node triggers the electrical impulse, causing the upper chambers (atria) to contract. The signal travels through the atrioventricular (AV) node to the atrioventricular bundle, which divides into the Purkinje fibers that carry the signal and cause the lower chambers (ventricles) to contract. The electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) shows this normal electrical activity.

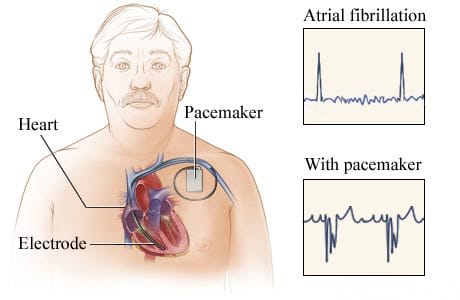

In atrial fibrillation, erratic electrical impulses in the upper chambers of the heart (atria) cause those chambers to fibrillate, or quiver. This results in an irregular and frequently rapid heart rate. The irregular, sawtooth pattern in the electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG) shows these erratic impulses.

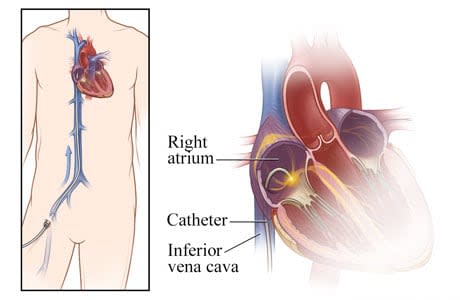

For this nonsurgical procedure, catheters are inserted into a vein, typically in the groin or neck, and threaded through the vena cava vein into the right atrium of the heart.

An electrode at the tip of the catheter sends out energy—such as radio waves, very cold temperatures, or laser light—that destroys (ablates) the atrioventricular (AV) node or other heart tissue that is responsible for the erratic impulses.

When the AV node is ablated, a permanent pacemaker is implanted that paces the ventricle. The pulse generator and battery part of the pacemaker are implanted under the skin of the chest. The electrocardiograms (EKG, ECG) show the heart's electrical activity during atrial fibrillation and when a heart has a pacemaker.

What To Expect

You may stay in the hospital overnight. You may have swelling, bruising, or a small lump around the site where the catheters went into your body. You can do light activities at home. Don't do anything strenuous until your doctor says it is okay. This may be for several days.

Many people think that having ablation means they'll be able to stop taking an anticoagulant every day to prevent stroke. But that is only true if your risk of stroke is low. Studies haven't proved that ablation for atrial fibrillation lowers your risk of stroke. So you'll still need to take an anticoagulant if your risk of stroke remains high. Your doctor can tell you about your stroke risk.

After an ablation, you might take an antiarrhythmic medicine for a few months to help keep your heart in a normal rhythm.

Your doctor might ask you to take your pulse at home to see if it's irregular. You might also use an ambulatory EKG monitor (such as a Holter monitor) at home to check your heart rhythm.

You might feel symptoms, such as palpitations, after the ablation procedure. These symptoms might happen while your heart is healing. Sometimes the symptoms may feel different to you after the ablation compared to before the ablation. During your follow-up visits, tell your doctor if you have symptoms. If they don't go away after a few months, you may choose to have a second ablation procedure.

Why It Is Done

Ablation is done to stop atrial fibrillation from happening and to relieve symptoms.

You and your doctor can check a few things to see if ablation is a good choice for you. These things include:

- What type of atrial fibrillation you have (paroxysmal or persistent).

- How bad your symptoms are.

- If you have heart failure or a problem with the structure of your heart.

- If you have tried heart rhythm medicines already. Your symptoms may not have gone away or you had side effects that are hard to live with.

The choice to have catheter ablation also depends on what you want.

Catheter ablation does have some serious risks, but they are rare. Many people decide to have ablation because they hope to feel much better afterward. That hope is worth the risks to them. But the risks may not be worth it for people who have few symptoms or for people who are less likely to be helped by ablation.

How Well It Works

Catheter ablation can stop atrial fibrillation from happening and can relieve symptoms. Your doctor can help you decide if ablation is a good choice based on your health.

Catheter ablation works better in people who have paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (episodes last 7 days or less) than in people who have persistent atrial fibrillation (episodes last more than 7 days). For both types, episodes may go away on their own or they go away after treatment. Ablation might be less likely to work the longer a person has persistent atrial fibrillation.

Things that limit how well catheter ablation works include older age and some health problems. You can help lower the chance of atrial fibrillation coming back by having a heart-healthy lifestyle and managing other health problems.

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

Research shows that ablation stops atrial fibrillation from happening for at least 1 year in about 60 to 90 out of 100 people. That means it does not help in about 10 to 40 out of 100 cases.

Persistent atrial fibrillation

Research shows that ablation stops atrial fibrillation for at least 6 to 12 months in about 60 to 80 out of 100 people. That means it doesn't work in about 20 to 40 out of 100 cases.

Repeated ablation procedures

Atrial fibrillation sometimes returns after an ablation.

If the first procedure doesn't get rid of atrial fibrillation completely, you may choose to have it done a second time. Repeated ablations may have a higher chance of success.

Risks

Most people do well after a catheter ablation. But it does have some risks.

Your doctor can help you decide whether the possible benefits of ablation outweigh these risks.

Problems during the procedure

If problems happen during or soon after the procedure, your doctor is prepared to fix them right away. Problems that need treatment happen in about 5 out of 100 people. These problems include bleeding, an accidental hole in the heart, and nerve damage in the chest.

Rare problems include cardiac tamponade and stroke. They happen in about 1 out of 100 people. This means that they do not happen in about 99 out of 100 people.

Death from the procedure is rare, happening to fewer than 1 out of 100 people.

Problems after the procedure

Problems after the procedure can be minor (such as mild pain) or serious (such as bleeding). Your doctor will check you closely after the procedure.

The most common problems are related to the catheter that was inserted in a vein. Many of these vein problems aren't serious. They include minor pain, bleeding, and bruising. But some problems, such as bleeding, need treatment. Bleeding that needs treatment happens in about 3 out of 100 people. This means that it doesn't happen in about 97 people out of 100.

Serious problems are rare. An example is a life-threatening problem with the esophagus (atrio-esophageal fistula) that happens to fewer than 1 out of 100 people.

Credits

Current as of: October 2, 2025

Author: Ignite Healthwise, LLC Staff

Clinical Review Board

All Ignite Healthwise, LLC education is reviewed by a team that includes physicians, nurses, advanced practitioners, registered dieticians, and other healthcare professionals.

Current as of: October 2, 2025

Author: Ignite Healthwise, LLC Staff

Clinical Review Board

All Ignite Healthwise, LLC education is reviewed by a team that includes physicians, nurses, advanced practitioners, registered dieticians, and other healthcare professionals.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Learn how we develop our content.

To learn more about Ignite Healthwise, LLC, visit webmdignite.com.

© 2024-2026 Ignite Healthwise, LLC.